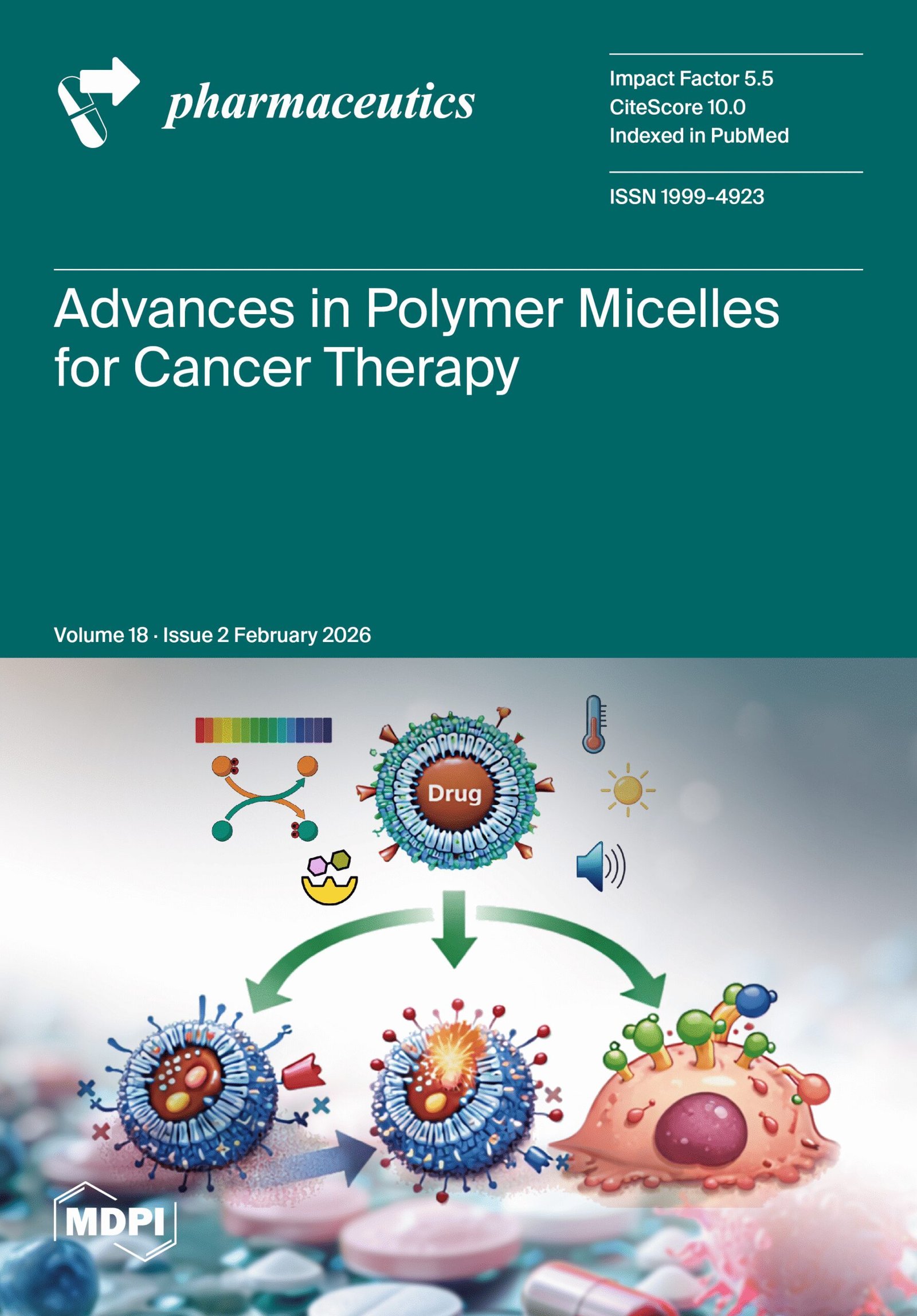

Skin cancer remains the most incident cancer in Brazil and worldwide. Although cure rates are high when detected early, conventional therapies – which involve surgery or chemotherapy – carry a significant burden for the patient: the risk of aesthetic mutilation and toxicity that affects the entire body.

A literature review article recently published in the scientific journal Pharmaceutics (2026, v. 18, n. 2) sheds light, among other topics, on a promising strategy: the use of metallopharmaceuticals (metal-based drugs) applied topically and more efficiently. The article, authored by researchers from CEPID CancerThera, details how compounds of gold, silver, platinum, palladium, ruthenium, vanadium, and copper, when combined with nanotechnology, can act on skin tumors without harming healthy tissue.

“Classic skin cancer treatments are effective, but they have relevant limitations: surgery may leave an important aesthetic impact and systemic chemotherapy exposes the entire organism to the drug, which increases the risk of toxicity,” explains Dr. Fernanda van Petten Vasconcelos Azevedo, biomedical scientist and postdoctoral researcher associated with CancerThera, lead author of the aforementioned article entitled Navigating the challenges of metallopharmaceutical agents: Strategies and predictive modeling for skin cancer therapy (from the original in English).

According to her, it is necessary to demystify the idea that metals in Medicine are an absolute novelty, citing cisplatin as a historical example. However, current innovation for skin cancer lies in the administration strategy: “Instead of relying only on the systemic route, we seek metallopharmaceuticals designed for local action and combined with delivery systems to concentrate the effect on the cutaneous tumor and minimize exposure of the rest of the body. This approach seeks to unite antitumor efficacy, lower systemic toxicity, and functional/aesthetic preservation, which are clear priorities in skin tumors.”

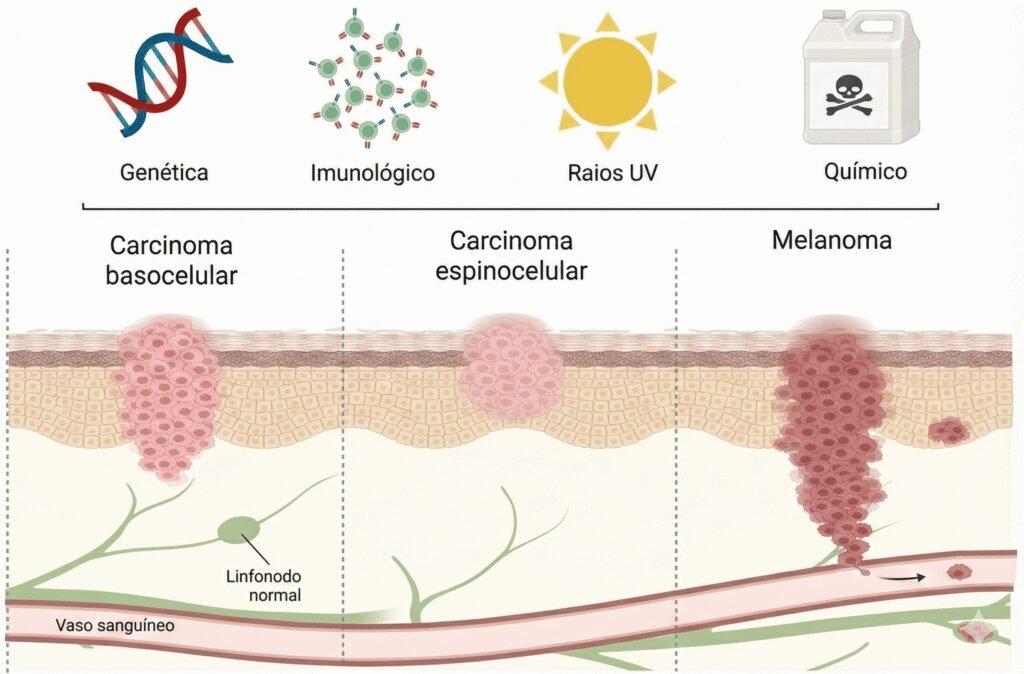

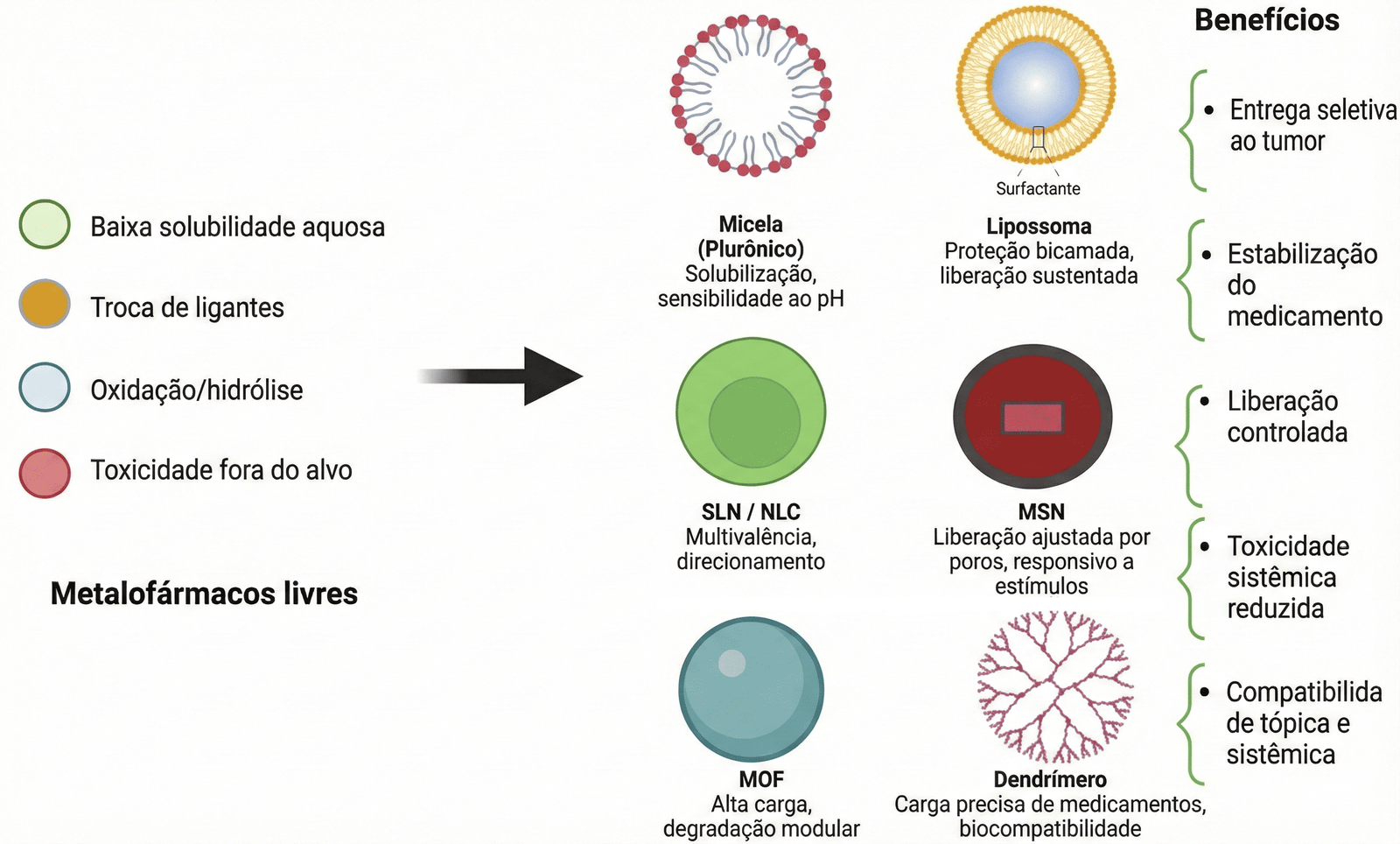

The article also describes advances in technologies that facilitate penetration into the skin and protect the integrity of these metals, such as hydrogels, microneedles, bacterial nanocellulose membranes, and nanoparticles (such as liposomes and micelles). In addition, the authors examine the role of photodynamic therapy and the use of mathematical and computational modeling to simulate drug transport and predict its distribution in the organism. The objective of these strategies is to unite physicochemical innovation with clinical application, enabling more selective, stable, and accessible treatments.

Overcoming barriers: microneedles and nanocellulose membranes

The review points out that the efficacy of metallic compounds lies in their ability to generate a fatal imbalance within tumor cells. While healthy cells can handle certain metal loads, tumor cells, which already operate at the limit, collapse. Azevedo details the mechanism: “Cancer cells already live under a lot of stress because they grow quickly and function in a disorganized way. Metallic compounds further increase this internal stress – a process called ‘oxidative stress’ – which impairs the normal functioning of the tumor cell.” She adds that these compounds damage the DNA of the cancer cell, preventing its multiplication: “With the accumulation of internal stress and DNA damage, the tumor cell loses control of its survival mechanisms and ends up dying. Because cancer cells are more sensitive to this type of damage than normal skin cells, this mechanism allows preferential targeting of the tumor.”

The superficial origin of the main types of skin cancer, such as carcinomas and melanoma, favors the application of local treatment strategies, allowing potent drugs, such as metallopharmaceuticals, to be directed specifically to the lesion. By concentrating the action of the drug in the tumor area, it is possible to increase therapeutic efficacy and, simultaneously, prevent the substance from circulating throughout the organism, which reduces systemic toxicity and ensures greater patient safety.

However, the challenge of topical application (in creams or patches) is to overcome the outermost layer of the skin, the stratum corneum, which acts as a protective barrier. “In the case of metallopharmaceuticals, physicochemical factors, such as molecular size, electrical charge, solubility, and chemical stability, may limit their penetration. Even compounds with high antitumor activity may have difficulty crossing the skin in sufficient quantity to reach the tumor,” emphasizes the biomedical scientist.

To overcome this, the article lists physical technologies such as microneedles – tiny devices that create painless channels in the skin. “In the treatment of skin cancer, microneedles facilitate localized and controlled delivery of metallopharmaceuticals, helping to overcome the skin’s natural barrier. They are considered promising because they cause minimal discomfort and pain when compared to traditional injections,” states the researcher.

Another technological front addressed in the article is the use of bacterial nanocellulose membranes. A research group active at CancerThera has already achieved preclinical success with a silver and nimesulide complex incorporated into these membranes, which function as a therapeutic “patch.”

Dr. Carmen Silvia Passos Lima, oncologist and hematologist, professor at the School of Medical Sciences of the State University of Campinas (Unicamp) and principal investigator at CancerThera, highlights the efficiency of this system in maintaining treatment. “The bacterial nanocellulose membranes used in a previous study conducted by us are of great importance, as they provide sustained release of equivalent doses of the drug – in this case, the silver complex – over the tumor,” she explains. “This means that it is not necessary to replace the patch frequently, thus saving financial resources without losing treatment efficacy,” she evaluates.

The future is digital and clinical

The article also highlights the importance of mathematical and computational modeling to predict how far the drug penetrates into the skin – optimizing doses even before biological testing – and to demonstrate which new drugs may be indicated for the treatment of superficial or deep skin tumors: “The models developed to predict the depth the drug reaches in the skin are of great interest, as they may spare conventional drug permeability studies in synthetic membranes that simulate human skin or in animal skin,” Lima points out.

The researcher further states that it is essential for these models to be validated by conventional assessments of drug penetration into skin layers (such as those mentioned) and in preclinical studies in small animals so that only then can they be used in clinical practice.

Regarding the arrival of these innovations to patients, the professor reveals that science is already moving from the bench to the hospital. “Considering that we have already observed that the nanocellulose membranes impregnated with the silver complex were effective, substantially reducing tumor size, and proved to be safe in mice (devoid of local or systemic toxicity or with acceptable toxicity), the next step is the clinical study – in humans.”

This study, she reports, is already being conducted at the Clinical Hospital of Unicamp by CancerThera researchers in patients with skin tumors – specifically squamous cell carcinoma. Led by pharmacist and postdoctoral researcher Gisele Goulart da Silva and under Lima’s supervision, the study comprises two phases: the first will verify the appropriate dose of the silver complex in nanocellulose membrane to be administered to patients; the second will evaluate treatment efficacy.

“The patches impregnated with the silver complex will only reach pharmacies and hospitals if the results of the clinical study indicate that the treatment is effective and safe for use in humans and after approval by the National Health Surveillance Agency (Anvisa),” Lima warns.

Metallic curiosities

- It is not just jewelry: In addition to gold and silver, metals such as ruthenium, copper, and vanadium are being explored in drug composition. Each has a different chemical “signature,” allowing attacks on tumors that have developed resistance to common treatments.

- The skin is a shield: The stratum corneum, the outermost layer of the skin, has an approximate thickness of a sheet of tissue paper (10 to 20 micrometers), but it is incredibly efficient in preventing the entry of substances. That is why technologies such as microneedles are essential.

- Bacterial “weavers”: The nanocellulose used in the dressings mentioned in the study is produced by bacteria (such as those of the genus Komagataeibacter). They weave a network of extremely pure fibers, much thinner than a strand of hair, capable of retaining water and medication, creating an ideal environment for treatment.

- Needles that disappear: Some of the microneedles mentioned in the study are “dissolvable.” Made of biocompatible polymers, they penetrate the skin, release the necessary metallopharmaceutical load, and disappear without leaving residues, eliminating hospital waste from sharps.

Authors of the article

Fernanda van Petten Vasconcelos Azevedo | School of Medical Sciences, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil.

Ana Lúcia Tasca Gois Ruiz | School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Campinas, Campinas, Brazil.

Diego Samuel Rodrigues | School of Technology, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil.

Douglas Hideki Nakahata | Donostia International Physics Center – DIPC, Donostia, Gipuzkoa, Spain.

Raphael Enoque Ferraz de Paiva | Donostia International Physics Center – DIPC, Donostia, Gipuzkoa, Spain; and Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Sciences, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Cerdanyola del Vallès, Barcelona, Spain.

Daniele Ribeiro de Araujo | Department of Biophysics, Paulista School of Medicine, Federal University of São Paulo (Unifesp), São Paulo, Brazil.

Ana Carola de La Via | Center for Natural and Human Sciences, Federal University of ABC (UFABC), Santo André, Brazil.

Wendel Andrade Alves | Center for Natural and Human Sciences, Federal University of ABC (UFABC), Santo André, Brazil.

Michelle Barreto Requena | São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC), University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos, Brazil.

Cristina Kurachi | São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC), University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos, Brazil.

Mirian Denise Stringasci de Azevedo | São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC), University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos, Brazil.

José Dirceu Vollet-Filho | São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC), University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos, Brazil.

Wilton Rogério Lustri | Institute of Biosciences, University of Araraquara (Uniara), Araraquara, Brazil.

Vanderlei Salvador Bagnato | São Carlos Institute of Physics (IFSC), University of São Paulo (USP), São Carlos, Brazil.

Camilla Abbehausen | Institute of Chemistry, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil.

Pedro Paulo Corbi | Institute of Chemistry, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil.

Carmen Silvia Passos Lima | School of Medical Sciences, State University of Campinas (Unicamp), Campinas, Brazil.

Text: Romulo Santana Osthues